10. Multiple Turtles and for Loops¶

Quick Overview of Day

Explore how to instantiate more than one turtle object in the same program. Introduce the for loop, and use the range() function to simplify the creation of large for loops.

CS20-CP1 Apply various problem-solving strategies to solve programming problems throughout Computer Science 20.

CS20-FP1 Utilize different data types, including integer, floating point, Boolean and string, to solve programming problems.

CS20-FP2 Investigate how control structures affect program flow.

CS20-FP4 Investigate one-dimensional arrays and their applications.

10.1. Instances — A Herd of Turtles¶

Just like we can have many different integers in a program, we can have many turtles. Each of them is an independent object, and we call each one an instance of the Turtle type (class). Each instance has its own attributes and methods — so alex might draw with a thin black pen and be at some position, while tess might be going in her own direction with a fat pink pen. So here is what happens when alex completes a square and tess completes a triangle:

Here are some How to think like a computer scientist observations:

We could have left out the last turn for alex, but that would not have been as satisfying. If you’re asked to draw a closed shape like a square or a rectangle, it is a good idea to complete all the turns and to leave the turtle back where it started, facing the same direction as it started in. This makes reasoning about the program and composing chunks of code into bigger programs easier for us humans!

We did the same with tess: she drew her triangle and turned through a full 360 degress. Then we turned her around and moved her aside. Even the blank line 21 is a hint about how the programmer’s mental chunking is working: in big terms, tess’ movements were chunked as “draw the triangle” (lines 15-20) and then “move away from the origin” (lines 22 and 23).

One of the key uses for comments is to record your mental chunking, and big ideas. They’re not always explicit in the code.

10.1.1. Mixed Up Programs¶

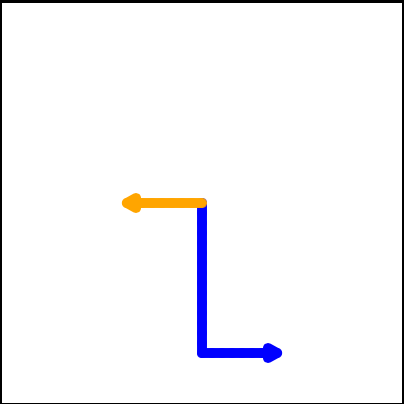

The following program has one turtle, “jamal”, draw a capital L in blue and then another, “tina”, draw a line to the west in orange as shown to the left.

The program should do all set-up, have “jamal” draw the L, and then have “tina” draw the line.

Drag the blocks of statements from the left column to the right column and put them in the right order. Then click on Check to see if you are right. You will be told if any of the lines are in the wrong order.

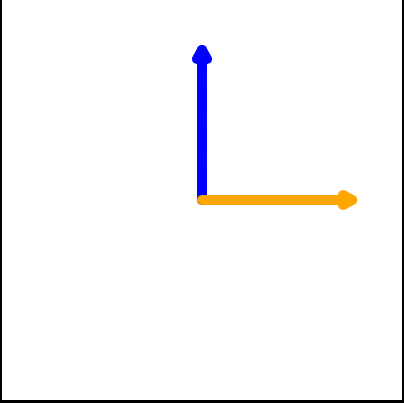

The following program has one turtle, “jamal”, draw a line to the north in blue and then another, “tina”, draw a line to the east in orange as shown to the left.

The program should import the turtle module, get the window to draw on, create the turtle “jamal”, have it draw a line to the north, then create the turtle “tina”, and have it draw a line to the east.

Drag the blocks of statements from the left column to the right column and put them in the right order. Then click on Check to see if you are right. You will be told if any of the lines are in the wrong order.

10.2. The for Loop¶

When we drew a square yesterday, it was quite tedious. We had to move then turn, move then turn, etc. etc. four times. If we were drawing a hexagon, or an octogon, or a polygon with 42 sides, it would have been a nightmare to duplicate all that code.

As we have seen previously, using iteration to repeat code over and over can solve the copy/pasting code problem we encountered when drawing a square.

In Python, the for statement allows us to write programs that implement iteration. As a simple example, let’s say we have some friends, and we’d like to send them each an email inviting them to our party. We don’t quite know how to send email yet, so for the moment we’ll just print a message for each friend.

Take a look at the output produced when you press the run button. There is one line printed for each friend. Here’s how it works:

name in this

forstatement is called the loop variable.The list of names in the square brackets is called a Python list. Lists are very useful. We will have much more to say about them later.

Line 2 is the loop body. The loop body is always indented. The indentation determines exactly what statements are “in the loop”. The loop body is performed one time for each name in the list.

On each iteration or pass of the loop, a check is done to see if there are still more items to be processed. If there are none left (this is called the terminating condition of the loop), the loop has finished. Program execution continues at the next statement after the loop body.

If there are items still to be processed, the loop variable is updated to refer to the next item in the list. This means, in this case, that the loop body is executed here 7 times, and each time

namewill refer to a different friend.At the end of each execution of the body of the loop, Python returns to the

forstatement, to see if there are more items to be handled.

A codelens demonstration is a good way to help you visualize exactly how the flow of control

works with the for loop. Click on the Show CodeLens button in the example above. Try stepping forward and backward through the program by pressing the buttons. You can see the value of name change as the loop iterates through the list of friends.

Note

Although you might not want to worry about this yet, it is really useful to know that you can access any specific part of list by providing it’s index value in square brackets, such as some_list[2] (the first element has an index of 0, the second has an index of 1, etc). Consider the following:

names = ["James", "Malindu", "Michelle", "Zoe", "Eli", "Bree"]

print(names[0]) # prints James

print(names[3]) # prints Zoe

10.3. Iteration Simplifies our Turtle Program¶

To draw a square we’d like to do the same thing four times — move the turtle forward some distance and turn 90 degrees. We previously used 8 lines of Python code to have alex draw the four sides of a square. This next program does exactly the same thing but, with the help of the for statement, uses just three lines (not including the setup code). Remember that the for statement will repeat the forward and left four times, one time for each value in the list.

While “saving some lines of code” might be convenient, it is not the big deal here. What is much more important is that we’ve found a “repeating pattern” of statements, and we reorganized our program to repeat the pattern. Finding the chunks and somehow getting our programs arranged around those chunks is a vital skill when learning How to think like a computer scientist.

It is also important to realize that we could have used a while loop to accomplish the same drawing, and a version that does just that is below:

Notice that although this code does the same thing as the for loop version, it requires some extra code compared to the for loop version. Generally speaking, if you know ahead of time how many times a loop should iterate, you should use a for loop (for example, iterating 4 times to draw a square). If you don’t know ahead of time how many times a loop should iterate, a while loop is a better choice (for example, iterating until Reeborg had a wall in front of it).

Thinking back to the for loop version we saw above, the values [0,1,2,3] were provided to make the loop body execute 4 times. We could have used any four values. For example, consider the following program.

In the previous example, there were four integers in the list. This time there are four strings. Since there are four items in the list, the iteration will still occur four times. some_color will

take on each color in the list. We can even take this one step further and use the value of some_color as part of the computation.

In this case, the value of some_color is used to change the color attribute of alex. Each iteration causes some_color to change to the next value in the list.

10.3.1. Mixed Up Programs¶

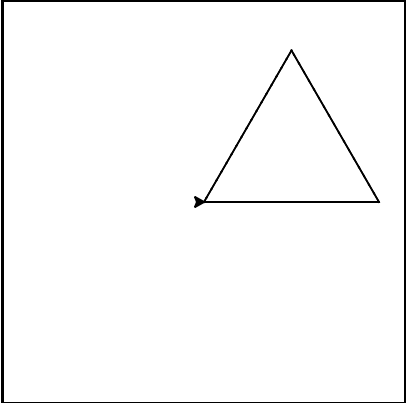

The following program uses a turtle to draw a triangle as shown to the left, but the lines are mixed up. The program should do all necessary set-up and create the turtle. After that, iterate (loop) 3 times, and each time through the loop the turtle should go forward 175 pixels, and then turn left 120 degrees.

Drag the blocks of statements from the left column to the right column and put them in the right order with the correct indention. Click on Check to see if you are right. You will be told if any of the lines are in the wrong order or are incorrectly indented.

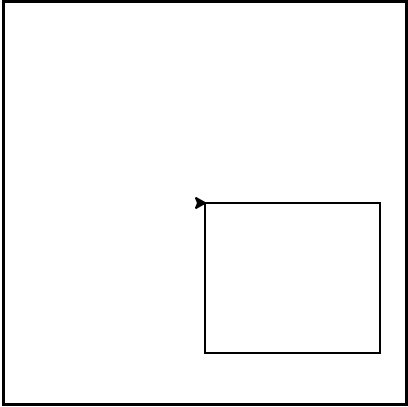

The following program uses a turtle to draw a rectangle as shown to the left, but the lines are mixed up. The program should do all necessary set-up and create the turtle. After that, iterate (loop) 2 times, and each time through the loop the turtle should go forward 175 pixels, turn right 90 degrees, go forward 150 pixels, and turn right 90 degrees.

Drag the blocks of statements from the left column to the right column and put them in the right order with the correct indention. Click on Check to see if you are right. You will be told if any of the lines are in the wrong order or are incorrectly indented.

Check your understanding

- 1

- The loop body prints one line, but the body will execute exactly one time for each element in the list [5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0].

- 5

- Although the biggest number in the list is 5, there are actually 6 elements in the list.

- 6

- The loop body will execute (and print one line) for each of the 6 elements in the list [5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0].

- 10

- The loop body will not execute more times than the number of elements in the list.

intro-for-loops11: In the following code, how many lines does this code print?

for number in [5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]:

print(f"I have {number} cookies. I'm going to eat one.")

- They are indented to the same degree from the loop header.

- The loop body can have any number of lines, all indented from the loop header.

- There is always exactly one line in the loop body.

- The loop body may have more than one line.

- The loop body ends with a semi-colon (;) which is not shown in the code above.

- Python does not need semi-colons in its syntax, but relies mainly on indentation.

intro-for-loops12: How does python know what statements are contained in the loop body?

- 2

- Python gives number the value of items in the list, one at a time, in order (from left to right). number gets a new value each time the loop repeats.

- 4

- Yes, Python will process the items from left to right so the first time the value of number is 5 and the second time it is 4.

- 5

- Python gives number the value of items in the list, one at a time, in order. number gets a new value each time the loop repeats.

- 1

- Python gives number the value of items in the list, one at a time, in order (from left to right). number gets a new value each time the loop repeats.

intro-for-loops13: In the following code, what is the value of number the second time Python executes the loop?

for number in [5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]:

print(f"I have {number} cookies. I'm going to eat one.")

10.4. The Range Function¶

It turns out that generating lists with a specific number of integers is a very common thing to do, especially when you

want to write simple for loop controlled iteration. Even though you can use any four items, or any four integers for that matter, the conventional thing to do is to use a list of integers starting with 0.

In fact, these lists are so popular that Python gives us special built-in

range objects

that can deliver a sequence of values to

the for loop. When called with one parameter, the sequence provided by range always starts with 0. If you ask for range(4), then you will get 4 values starting with 0. In other words, 0, 1, 2, and finally 3. Notice that 4 is not included since we started with 0. Likewise, range(10) provides 10 values, 0 through 9.

for i in range(4):

# Executes the body with i = 0, then 1, then 2, then 3

for x in range(10):

# sets x to each of ... [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Note

Computer scientists like to count from 0!

So to repeat something four times, a good Python programmer would do this:

for i in range(4):

alex.forward(50)

alex.left(90)

10.5. Practice Problems¶

Try the following practice problems. You can either work directly in the textbook, or using Thonny. Either way, be sure to save your solution into your Computer Science 20 folder when you finish!

You might find the Python Documentation for the turtle module to be helpful: https://docs.python.org/3/library/turtle.html.

10.5.1. Regular Polygons¶

Create a program that uses for loops to make a turtle draw regular polygons (regular means all sides the same lengths, all angles the same). First, ask the user how many sides they want the polygon to have, and how long each side length should be. Now draw the regular polygon that meets the user’s requirements!

Note

Remember that in a regular polygon, the sum of the exterior angles of the polygon will always be 360 degrees.

10.5.2. Draw a Star¶

Create a program that uses the turtle module to draw a five sided star. The user should be able to set a number of options each time the code runs, so the program should ask the user for:

the width of the turtles pen

the turtle color

the length of the sides of the star that will be drawn

the background color to use

One run of the program might produce a star that looks like the following:

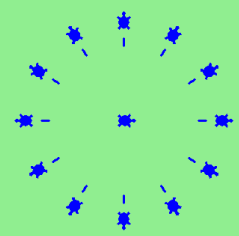

10.5.3. Drawing a Clock¶

Create a program that uses the turtle module to draw the shape of an analogue clock. Do this using ONLY ONE TURTLE object. It should look like the following:

You might need to explore the Turtle documentation on the Python Docs website to figure out how to leave an image of where the turtle was.